Prince Philip, whose funeral takes place this weekend, once said, “everything that wasn’t invented by God is invented by an engineer“. He was himself an engineer by training and this pithy line is a favourite among his fellow engineers.

It brilliantly captures the fact that the world around us is largely manufactured and that the genius of engineers comes not only in the process of fabrication, but in hiding the genius involved.

That said, the idea that everything not of the natural world (let’s leave God out of it for now) is the work of engineers is patent nonsense. On my wall is a painting. On my shelves, there are novels. Certainly, engineers are responsible for paints, for paper, for inks, for the printing presses, for computers and for so much else involved in delivering these products to me. But the artworks themselves are surely also something not of the natural world and yet invented?

Any writer who has had to invent characters, a plot or an elegant turn of phrase knows that ‘invention’ is not the sole preserve of God and engineers.

However, I think this leads us to a better understanding of what engineers really do. Engineers – like God* and artists – are creators.

To me, Philip’s comment belittles artists – albeit unintentionally. Instead of seeing engineering as applied science – or, worse still, fixing broken stuff – we should see engineering as an act of creation akin to the arts.

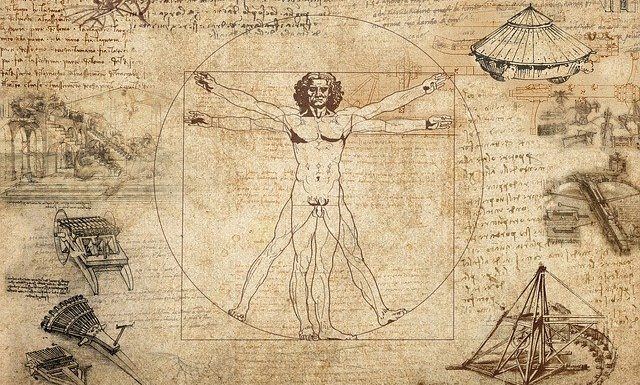

It was seen that way once upon a time. The relationship between the pure artist, the skilled craftsperson, the experienced artisan and the inventor was regarded as a continuum. We all know that Leonardo da Vinci was all these things, but so too were William Morris and Alec Issigonis. And today, the likes of Grayson Perry or Rachel Whiteread require the skills of their craft as much as James Dyson and Jonathan Ives need artistic vision.

The Duke of Edinburgh was a staunch champion for engineering, but his support failed to abate a crisis in the UK’s engineering skills pipeline. We have an estimated shortfall of 124,000 skilled engineers and technicians every year. The only way that this situation can be resolved is if the perception of engineering among young people – and young women in particular – is radically shifted.

Children and teens love to create – to build sandcastles, to paint, to play Minecraft or to express themselves through performance. They don’t see a distinction between drawing as ‘artistic’ invention and creating a Lego house as ‘engineering’ invention. Somehow, though, as a society, we beat this out of them, creating the idea that engineering is more about physics and maths than ingenuity and design.

Young people also care passionately about the problems we face – social challenges, environmental emergencies, sustainability. These are problems that – if humans can ever fix them – it will be through the efforts of, among others, engineers. Engineering offers young people an opportunity not only to be creators, but also to be world-saving superheroes.

Other countries tend to be better than the UK at never letting their young people lose sight of the creativity in engineering. We must learn to do better too. It is perhaps unfair to say the Duke’s comment inadvertently depicts the world as a place of opposition between humans engineers and natural wonders, but certainly we need to regard our human power to create – both beauty and design – as something that is not only in harmony with nature, but an active part of it.

* Or natural processes, depending on your religious perspective. I reference God because the Duke did.