What links oxbow lakes, metacognition and employability skills? We’ll get to that shortly.

But first, if you want to know what works in creating social opportunity through education, you’d be hard pressed to find a better expert than Lee Elliot Major, former chief executive of The Sutton Trust and now Exeter University’s professor of social mobility.

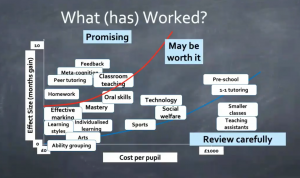

Yesterday he gave a lecture at the Institute of Education (well, virtually) in which one slide pretty much summed up the toolkit produced by the Education Endowment Foundation and the content of his own book (with co-author Steve Higgins) What Works. (Thanks to Lee for permission to use the slide below.)

I am delighted to see metacognition making an appearance as not only highly effective, but highly cost-effective too. Indeed, along with feedback (the two need to go hand in hand), these are the most cost-effective tools in the teachers’ box.

As anyone who has heard me talk about oxbow lakes knows, I have long been a metacognition fan.

I promise, I’ll get to the relevance of oxbow lakes in a moment, but first, what is ‘metacognition’? I’m sure there are more complex explanations, but I think of it as knowing what you’re learning. It is an awareness of the subject such that the pupil can learn deliberately, consciously, and with an understanding that they are learning, what they are learning and perhaps even why they are learning.

So why oxbow lakes? The National Curriculum for Key Stage 2 Geography requires students to learn about river erosion and so, basically, by the age of 11, English kids are officially expected to have learnt about them.

Strangely however, we don’t require children to lean about many things of potentially more practical use – such as Facebook privacy settings, pensions or laundry labels.

I’m sure oxbow lakes are important to some people, but it’s not like they’re a critical piece of knowledge for the next generation (and those those who do need the knowledge could acquire it later), so why do we demand pupils learn about them?

Well, I love oxbow lakes. I don’t think this is useless knowledge at all. After all, they teach pupils about time travel.

From one data point in the landscape, you can deduce what that landscape looked like thousands of years ago or predict how it will look like in a thousand years time.

By understanding the processes at work in forming an oxbow lake, you can see problems before they happen and even develop solutions to prevent those problems.

This is what we’re really teaching when we teach about oxbow lakes: analytical skills.

Analytical skills are key skills – useful in every walk of life. Definitely more important than laundry labels.

The problem is, we don’t tell pupils that that’s what they’re learning. We tell them it’s Geography.

How much more effectively would pupils develop the analytical skills if we made the learning explicit and deliberate? Metacognition, innit?

Embedding metacognition can be as simple as saying upfront that we’re about to practice some analytical skills and, to do it, we’re going to use the example of oxbow lakes. Sadly, our education system is not designed to encourage that.

We also need to build in reflection on – and feedback about – those skills after they’ve been exemplified and, obviously, we need to reapply them in different contexts in order to develop them further ensuring they are transferable.

If each time we develop those skills, we do so consciously – metacognitively – the connections will be made in the pupils’ minds.

The oxbow lake example is my perennial response to pupils who ask “Why am I learning this? I’m never going to need to know this?”

The answer is always to think more clearly about what we really learn when we learn.